Looking Maine Potatoes in the Eye

- by Karen Cummings

- Oct 2, 1986

- 6 min read

This spud's for you!

Do you know where your food comes from? Fruits and vegetables from California, butter from Minnesota, beef from the Midwest... When you sit down for your evening meal, you might not know where your steak or chicken was raised, what state your butter or your milk came from, on which coast your vegetables were grown, but when you bite into your potatoes, chances are pretty strong that they came from your own back yard.

No, your potatoes didn't come from way up in northern Maine in the famed Aroostook County, the area renowned for its production of potatoes. On the contrary, a large percentage of the Maine potatoes sold in area grocery stores are grown right here in the Saco River Valley.

"The prime land in this valley is the finest growing soil anywhere," said Don Thibodeau, a partner with Earl Towle in the Green Thumb potato farm in West Fryeburg. Originally from Aroostook County, Thibodeau and Towle much prefer the "milder" weather and longer growing season of this area of Maine. "Compared to other parts of the state, we have an early spring and a late fall,” explained Thibodeau. "They've already had a hard frost up there which freezes the soil and damages the potatoes closest to the top. We've only had a light frost and now with this warmer weather, the potatoes will just be getting bigger."

It's harvest time in the Maine potato fields. Potato planting here usually begins in middle to late April and continues for a month. "We start as soon as we can get out into the field," said Thibodeau. "In Aroostook County, they're happy if they can get started by the first of May." Harvesting starts as early as August and continues for several weeks into the fall.

The longer growing season is a distinct advantage for potato growers here in the more southern section of the state. "This a perfect place to grow potatoes," said Thibodeau, who plants from 475 to 500 acres in potatoes. "Potatoes like warm days and cool nights, plenty of water, and they need a fairly long growing season—all things that we have here most of the time."

Two other local farmers also deal primarily in potatoes, Doug Albert of Albert Farms, and Barry Hill of Hill Farms. Other potato growers lease prime bottom land around the valley, putting the total amount of acreage devoted to potato cultivation at more than 1000. With one acre yielding, on the average, 32,500 pounds of potatoes, it means that there is a sizeable harvest of spuds in this valley.

You may think potatoes need the northern climates to grow better, but that is not necessarily the case. Potatoes are grown during the winter in the south and those harvesting run into a similar problem as their northern counterparts when harvesting them. "We have to harvest them before winter so they won't freeze in the ground," said Thibodeau, "but in the south, as it starts getting warmer, they have to harvest them quickly to keep them from cooking in the ground."

Potatoes will grow almost anywhere. "More potatoes are grown in the north because they can be stored using natural refrigeration," explained Thibodeau, who stores more than 7000 tons of potatoes in the Green Thumb warehouses prior to packing. For this reason, potato production was pushed into the northern states where root cellars were the most efficient way to store the tubers.

Green Thumb Farms grow russet potatoes—the classic baking potato, round white (or eastern) potatoes, and potatoes suited for potato chip production.

The russet potatoes grown by Thibodeau and his partner are of the same variety as those promoted as an "Idaho potato." Asking what must be characterized as a potato grower's joke, Thibodeau said. "'What's the difference between an Idaho russet potato and a Maine russet potato?" Well, the answer is that one is grown in Idaho and the other is grown in Maine. In other words, there is no difference. “The western potato grower has put out a great ad campaign which makes people think there is something exclusive about an Idaho potato," added Thibodeau.

The majority of people in the east prefer the round white potato, the most popular variety grown in Maine. All purpose (it can be boiled, mashed, baked and fried), the round white prefers the soil in the east, which is less acidic than that in the west. "Most of our production is in round white potatoes,” said Thibodeau.

A less moist, less starchy type of potato is cultivated for potato chip production. "A potato is normally about 87 percent water," explained Thibodeau, "and potato chip manufacturers prefer a potato with more solids because then they absorb less oil during production." He went on to explain that when cooled, the starch in the potato converts to sugar which translates to a darker (and generally undesirable) chip, as the sugar content will burn during processing.

Yes, there's definitely more to the potato than meets the eye. There's also more to the harvesting and pack-ing of the potatoes than one would think, too.

August is the pivotal growing month for potatoes. It's our tonnage month." said Thibodeau. By the time the dog days of summer have rolled around, the leafy green part of the plant above ground has reached its full growth and the plant is putting its energy into the tubers. Sunshine is an important ingredient during this period. "Our yield this year isn't going to be as high as expected." added Thibodeau, "because August was such a cool and rainy month."

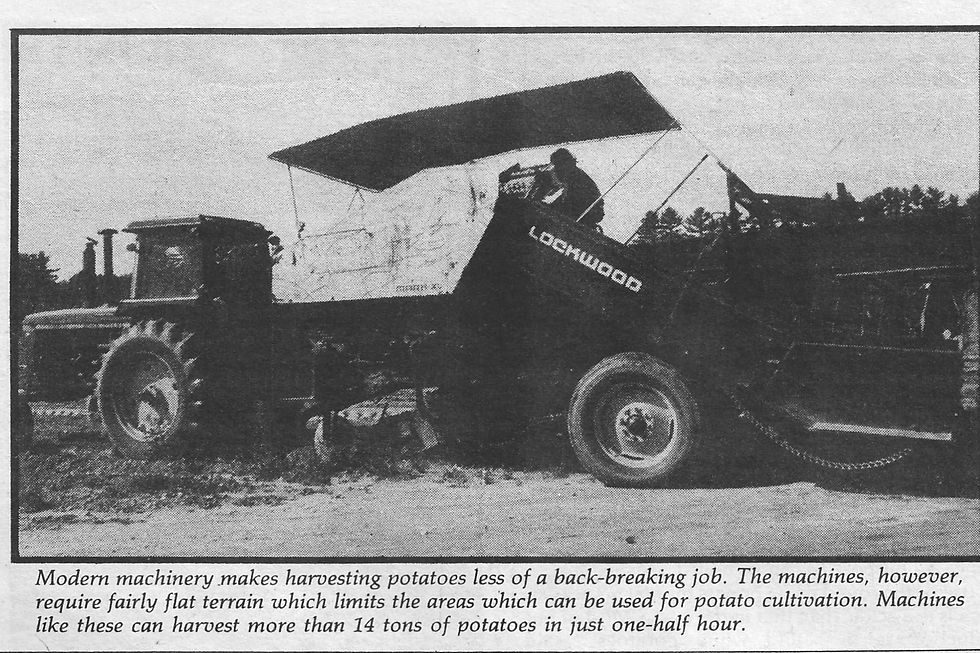

Nevertheless, all the potato farmers in the Saco River Valley have been busy harvesting for the past few weeks. Tractors and machinery have eliminated the backbreaking work of digging the tubers out of the ground. Happily growing in the fertile ground, the potato is now summarily plucked from its birthplace by a huge harvester which combs through the ground, lifting several rows of potato plants at a time (and sometimes some rocks).

Riding up several conveyor belts designed to separate the wheat from the chaff, or in potato language, the tuber from the chunks of dirt, rocks and plant stems, the potato makes its way to the truck riding alongside the harvester. Just before going up the final chute, the potato passes by human hands that pick away anything the machines missed just before it falls off into the truck which can hold anywhere from 12 to 16 tons of its fellow potatoes.

From there our Mr. Potato is transported to the warehouse. Once deposited in a bin, what happens next depends on the intended purpose of the individual potato, which, by the way, is considered an almost complete food, as it supplies protein, vitamin C, thiamine and nutrients which can be converted into vitamin A by the body.

At the Green Thumb Farm, potatoes are brought in by the truckload and put into huge storage bins as they wait their turn to be cleaned, computer sorted and packaged. The majority end up in 5- or 10-pound bags.

Somewhat like a beauty pageant, the first elimination for the potato comes even before it's been washed. Riding on a conveyor belt, the spuds have to pass over a grate which allows any potato smaller than two-and-a-quarter inches in diameter to fall through. Normally the minimum diameter for Grade No. 1 potatoes is an inch and seven-eighths, but Thibodeau reports that Shaw's, one of his big customers, insists that housewives don't want anything smaller than two and a quarter.

The tiny, dirty potatoes that don't make the grade are carted off, often to finish their life in potato salad, while their larger friends get to take a shower. Emerging clean from the intense sprinkler bath, the potatoes make their way to be sorted by computer laser, a "photo-sizer," which determines each potato's size and sends it down the appropriate chute into a waiting box. Or, if it isn't too large or too small, the potato is sent onto another belt that brings the sparkling clean spud to the bagging department.

The really huge potatoes, which would fill up a plate if served at a meal, have been sorted out, usually to be sent to a processor that converts them to French fries or frozen baked/stuffed potatoes. This leaves the majority of the potatoes to face the final elimination. No longer entrusted to machines, this quality control examination is conducted by people who meticulously look for bruises, growth splits, sun scald, and all the other horrible things that can afflict the potato. These so-called seconds, which are perfectly edible if the defect is just cut away, are sold as U.S. Grade No. 2 potatoes in 50-pound bags for only $3.50.

The rest of the potatoes, which have passed all the tests, are then bagged ready for shipment to waiting supermarkets, some as far away as Philadelphia, or Florida. "Tastes in potatoes are regional," explained Thibodeau, "with New Englanders definityely preferring the round white."

So that's the story of the lowly potato which was first cultivated in South America, brought back to Europe by the early explorers, then introduced in North America by the first settlers. Although Maine's production of the potato has steadily decreased over the years due to competition from growers in the western United States and Canada, production in the valley has remained steady or increased.

If you happen to be an average American who, statistics say, consumes more than 100 pounds of what the French call the apple of the earth, isn't it reassuring to know there are still plenty of potatoes being grown right here in our valley?

Editor’s Note: While this story was written in 1986 and many things have changed since then including some info in this story, Green Thumb Farms is still growing potatoes and still family run. Learn more About | Green Thumb Farms.

Comments