The Grande Age of Hotels

- by Tom Eastman

- Jul 6, 1979

- 7 min read

"The pure air, water, and cool weather of the White Mountains, the exceptional comfort and luxury of its fine, large hotels, and the quick and easy transportation by rail and coach to and from them, particularly from New York and Boston, make these resorts very prominent this year in the eyes of those seeking pleasure and comfort this summer." These words are taken from the pages of a tourist advertising book from the 1880's.

Today, the pure air, water and cool weather remain, but the great, rambling wooden inns that were once so easily traveled to are, for the most part, gone. At the turn of the century, when the great hotels were enjoying their "Golden Era," there were over 100 in the White Mountains alone. Of those grand landlocked ocean liners, only eight are standing today, and only four still operate as hotels. The rest of the huge structures which once served as the summer residences of the wealthy have all either been torn down or else have been the victims of fire, some of them of the "Midnight lightning" variety, it is supposed. Their story is one of an era and lifestyle now passed and never to return; a glimpse of a time already fading from the consciousness of those who never saw it to begin with, and those who are no longer here to remember.

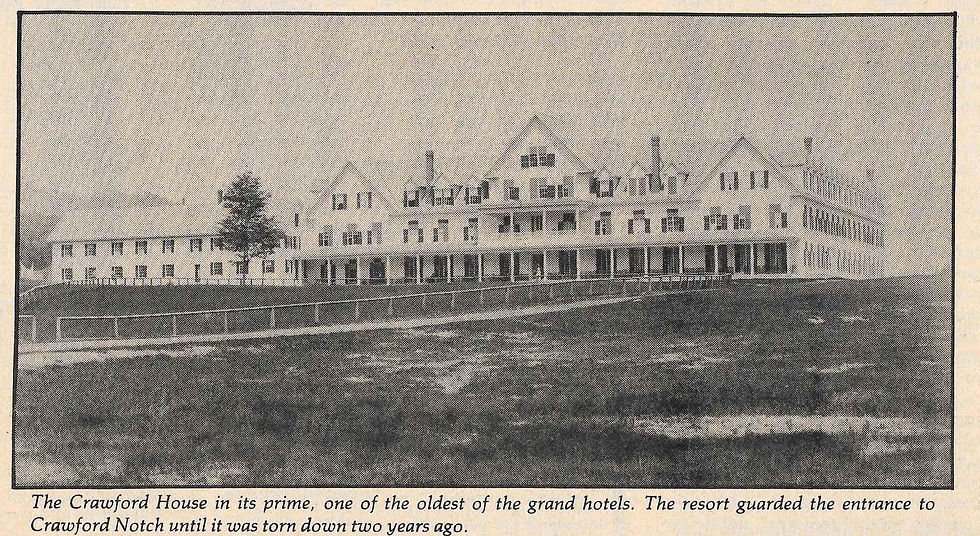

The Golden Era lasted between the years of 1865-1910. The hotels catered to the wishes of those for whom money was no object and for whom extravagance was commonplace. The White Mountains were the place to be for the social set of New York and Boston, a set whose members included the names of such families as the Rockefellers and the Duponts. One of the grandest of the grand hotels, the Crawford House that until two years ago [1977] stood at the top of Crawford Notch, was visited by six U.S. presidents. Other dignitaries that visited other inns in the region included native son Daniel Webster, William Wadsworth Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Thomas Edison.

There have always been tourists traveling to see the beauty of the White Mountains, but in the first half of the 19th century, they had to go through quite a journey by rail, steamboat, and finally stagecoach to get to the area. The coming of the railroads to the mountains changed all that, though, and in 1852 rail service reached the towns of Gorham and Littleton. Soon thereafter, the original Crawford House, the Profile House in Franconia, the Alpine House, and the Glen House near the base of the present Auto Road up Mt. Washington, opened to take in the passengers the railroads were carrying into the region. The railroads expanded rapidly, and the rail companies actually built many of the grand hotels to ensure that their tracks would be put to use.

The arrival of railroads to North Conway, Lincoln, and Twin Mountain in the 1870s resulted in the building of more hotels to accommodate the increasing number of tourists, many of whom were already seeing different areas of the country for the first time. The new American appetite for mobility, whetted by the railroads and responsible for the popularity of the summers inns, eventually would lead to the downfall of the railroads themselves and indirectly to the inns as well, once the automobile became available to the affluent and near affluent Americans. But in the Golden Era preceding that eventuality the great hotels prospered.

Hotels of 50 to 250 rooms were common and nearly every town in the mountains had at least one. The hotels boasted of their gardens, tennis courts, and golf courses, as well as their views of the Presidential and Franconia Ranges. They were renowned for the great length of their customary mammoth porches, the size of their dining halls and ballrooms, too, and also for the fact that their streets were kept cool by a sprinkler system during the hot days of summer to afford more pleasurable walking of their guests. The presence of a post office could lend great prestige to an inn, and at the turn of the century there were 15 of these fashionable inns in the White Mountains.

One of the first hotel chains established in the White Mountains during the era was operated by the Barron, Barron & Merrill Hotel Company. At one time, the father, son and partner team owned the Crawford House, Fabyans in Twin Mountain, and operated the Mt. Pleasant House and the Summit House, the hotel located for a time on top of Mt. Washington. A later hotel magnate in the White Mountains, Karl P. Abbot, became the first multi-state hotel owner, with the Profile House, the Upper Terrace in Bethlehem, and the Forest Hills in Franconia, which was until recently the home of the now defunct Franconia College. Abbot owned other hotels in North Carolina and Florida as well.

Eating in the grand dining halls of the inns was often an extravagant two-hour affair, with a resident orchestra comprised of vacationing symphony musicians playing for the dinner guests. The menus featured the best delicacies to be found on either side of the Atlantic, and often all the vegetables, cream, and other dairy products used for the meals were from the more prestigious inns' own grounds. The inns were self sufficient, for that matter, for many of their needs, with their own printing presses, telephone systems, and electric generators.

One of the more difficult social problems involved with dining was in the seating of the guests. The problem was magnified by the fact that many of the guests were regulars at the inns, and would therefore be stuck with the same seat from year to year. The Mount Washington Hotel was one of three inns to solve the problems of high-ranking guests complaining of being seated in dark corners by designing an octagonal dining room. The Mount Washington, which was one of the last of the truly great hotels built, is one of the four still operating as a hotel. Its dining room is 84.8' by 84.8', and one of its other notable features is that it was the first hotel in New England to have an indoor pool, and it also was built with its own Turkish baths. The hotel was the site of the 1944 Bretton Woods International Monetary conference.

For entertainment, the inns offered concerts by the residential orchestras at afternoon tea-time, and also held nightly balls in their large ballrooms. Carriage trips up the Mt. Washington Auto Road and rides on the Cog Railway were also popular, as were visits to the Flume, the Old Man of the Mountains, and to the other inns.

During the later years of the era, the expansion of rail lines allowed for convenient and easy use of trains between inns, and many families stayed at a different inn each week, something which in the past had been impractical.

Baseball contests between the staffs of the inns were also popular as entertainment for the guests. Another contest staged each summer was the Coach Parade, where the hotels vied for supremacy in their carriages with elaborate decorations, spending over $1,000 to outdo their rivals. The contest usually was held in Bethlehem, where the tree-lined streets would be decked out with bunting for the gala event.

All of the inns had special quarters for the hired personnel of both the guests and the inn, and the Wentworth Hall in Jackson discreetly mentioned in an advertisement that their inn had servants' quarters located "some distance from the main house." The inns were built for service, and many of them had a ratio of one staff member per guest, with the average earning for a waitress for the entire summer being $300. As times changed, the large staff was no longer affordable and the special service the inns built their reputations on no longer was economical. As a result, they were no longer able to attract the wealthy customers they had catered to before, and the maintenance of the majority of them suffered to the point that once majestic flagships of the mountain glens became eyesores or second-rate hotels.

Then automobile changed the American style of tourism, with greater emphasis placed on traveling and less on staying in one favorite place. The railroads and their passenger service, once responsible for transporting the wealthy from their city homes in Philadelphia and New York to the inns, lost out to the cars, and the inns lost along with them.

It is rumored that many of the inns were torched for insurance reasons. Others, like the Profile House and Glen House, burned before their time, with the spectacular Profile House blaze of August 1923 signalling the true end of the Golden Era. The Kearsarge House, once located where the Community Center now stands near the park and railroad depot in North Conway, also burned, as did the Randall, Intervale, Fabyans, Maplewood, Sinclair and numerous others. The Jackson Falls House, long a landmark but recently a run-down sight in the village of Jackson, was auctioned off and bulldozed down this spring. A level plot of fresh dirt sits where the inn once stood near the Town Hall.

In addition to the Mount Washington, the others still operating are the Eagle Mountain House in Jackson, the Mountain View House in Whitefield, and the Balsams in Dixville Notch. The others still standing but now vacant, boarded up with peeling paint, are the Wentworth Hall [now fully renovated] and Grays' Inn in Jackson, the Forest Hills in Franconia, and part of the original Waumbek Inn in Jefferson. Their former glorious past is gone, but some see a trend back toward the destination resort style vacation on which the inns prospered, though not in the gilded extravagance of the earlier era, a time when money was no object for some and when gasoline had little value as a transportation fuel for most.

NOTE: Special appreciation to Dick Hamilton of the White Mountains Attractions Association for his assistance with this article.

Comments