Nature in its Rarest Mood - Winter Mountaineering

- Karen Cummings

- Jan 26, 1979

- 6 min read

Winter weather in the mountains of New England is rarely kind. The stark, frigid environment, particularly above timberline, can be extraordinarily beautiful, though, and inevitable outdoors enthusiasts are drawn from warmer surroundings to participate in the very different experience of winter hiking.

"Above timberline in winter you see nature in its rarest mood, expanses of untouched snow, and amazing hoar frost," remarked Bill Aughton, of International Mountains Equipment. "There's more of a sense of accomplishment than in summer hiking," added Rick Wilcox, manager of Eastern Mountain Sports in North Conway. "It's not all fun, or easy. You have to have a positive desire and attitude, but it's worth it in the end."

The Presidential and Franconia Ranges of Northern New Hampshire, to mention only several possibilities, afford excellent opportunities for winter hikers, and are quite accessible. A venture of this sort is not a casual encounter, however. "It's not a game," Bill emphasized. "It's probably easier to end up in the hospital hiking above timberline than ice climbing." One key is not to attempt such a climb until after extensive winter hikes at lower altitudes. Even after that, common sense dictates traveling with a guide on your first outing, or an experienced winter climber who'll act as group leader.

Knowing and appreciating the ferocity and changeable nature of the weather is also a necessity. check the forecast before you leave. An apparently fine day may be the harbinger of foul weather, and it's important to know what to expect. Also, find out the conditions above timberline. Deep snow dictates the use of snowshoes, while more often a pair of 10- or 12-point hinged crampons will be required for sure footing once you're up top.

A trip begins long before you actually start up the trail. Sit down and figure out what you'll need for equipment, or better still, ask an expert, and then assemble your gear the night prior to the hike. "Don't assume someone else has the first aid kit or some other essential," Rick said. "Make sure it's there before you leave." It's also important to carry enough equipment in case you have to spend an unexpected night out.

"The idea is to carry the minimum amount necessary, and still survive if something drastic happens," Bill noted. "Don't go light. Anything can happen." Among the essentials are a bivouac bag, or windproof sleeping sack, extra food, dry clothing, a sleeping bag, matches and a flashlight. "There's an art to spending the night out in winter, and people who go above treeline have to know what it involves." he added.

Proper dress for a winter climb consists of the classic layers of wool; underwear, shirts, sweaters, pants, and then windpants, a shell and parka. Once underway, you'll soon discover how warm wool really is, and winter hiking is a constant battle to regulate body temperature in order not to sweat too profusely, or your clothes freeze to your body. The major advantage of wool, of course, is that it retains body heat even when wet.

More difficult to choose is proper footwear. Double boots are ideal, and highly recommended, but also extremely expensive, perhaps prohibitively so for all but the frequent visitor to the high country. A regular pair of hiking boots will keep you warm while you're moving, especially if they're loose with several pairs of socks, but are inadequate if it's necessary to be stationary for any length of time. A satisfactory compromise are overboots, which slip over regular climbing footwear, and provide good protection from the cold plus mobility.

Sorrels or Mickey Mouse boots are also commonly used above treeline, and are ideal for snowshoeing when the peaks are covered with drifted snow. They are definitely not designed for crampons, however, and as Rick pointed out, the most common cause of accidents above treeline is improper combinations of footwear. Crampons cannot be strapped tightly enough to flexible boots to be really secure, though if you try this method, you may succeed in cutting off proper circulation to your feet, causing frostbite. Otherwise, the crampon can easily slip around to the side of your boot, or under extreme pressure may even cause them to break. In either case, the result can be a serious fall. Crampons are designed to be worn with heavy boots with a still sole, and it's of the utmost importance that both the boot and crampon are a good fit. "It makes a lot more sense to check them before you start, than to find out once you're up top," Rick remarked.

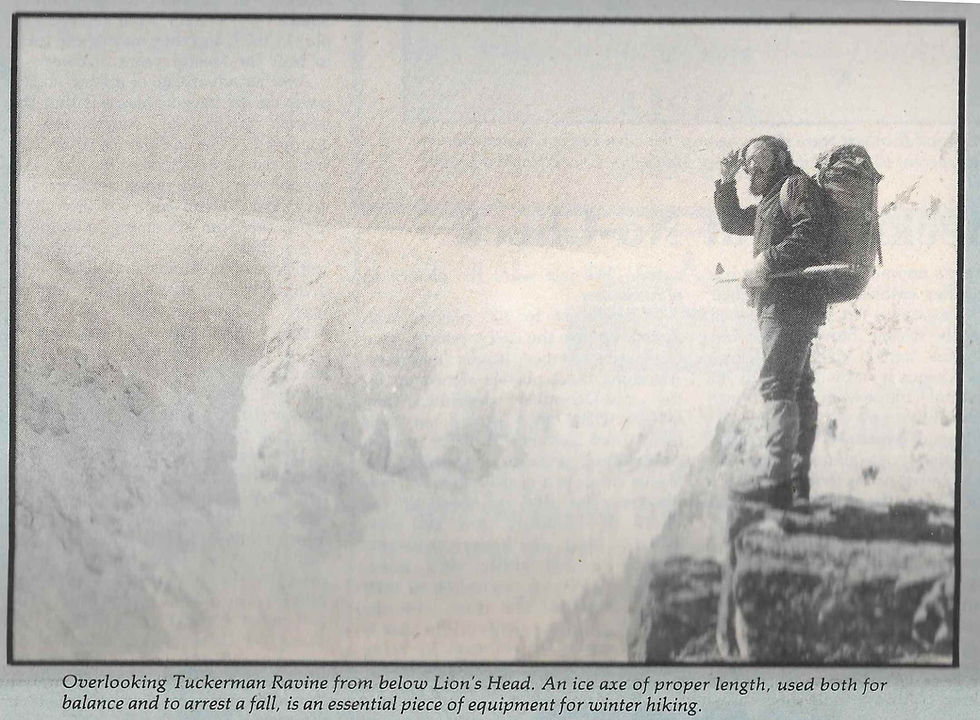

An indispensable traveling companion above timberline is an ice axe of decent length, both for balance and to brake with in the event of a fall. Even the best climbers can take a spill, Rick noted, and it's essential to know how to use your axe before an emergency situation occurs. Any reasonable sheet of ice or even a toboggan run will do to practice on, he elaborated, and as you begin to descend on your back, the proper reaction is to roll over with the ice axe diagonally across your chest and to drag the tip in the frozen surface.

Goggles are important, too, since wind is an ever present part of life above treeline. "Sunglasses can be impractical, or may blow away," Bill said. "Beside, snow blindness is fairly uncommon in New England, where vast expanses of snow, unbroken by rocks, are rare. Goggles, on the other hand, shield your eyes from windburn and blowing snow." Facial protection is another necessity, either a ski mask, balaclava or leather mask. "With a face mask and goggles you can look into anything or any wind," Bill said.

Windchill is much discussed, though its significance is sometimes overrated. "Windchill is a measure of the reaction of temperature against the skin," Bill explained. "Obviously, if you're well covered, it won't be that much of a problem, It's more important sometimes that that the temperature is -20 degrees, than 10 degrees with a 50 mph wind," he continued. "That kind of cold is much more penetrating, and you can't get away from it. It's not the wind that does the damage, but the basic temperature."

Even if an outing has been well planned, the unexpected can occur, and as Bill pointed out, a part of mental preparation is knowing what you'll do in an emergency. If at all possible, get down off the mountain, and at the very least below treeline. If it's not possible to reach help, foremost is to get low, dry and out of the wind, and to insulate yourself from the snow and ice. One method is to stamp a spot in the snow, preferably at the base of a tree, and then put down a sleeping bag, pack, or as a last resort, boughs. In this manner, even under extreme condition, it's quite possible to weather a night out, granted an uncomfortable one, or survive until help arrives. "A snow shelter or cave may be ideal in theory, but mighty hard to build if you're hurt or sick," Bill added.

Frostbite is an imminent enemy once you're stationary. "Of course, if there's any way possible, you should try to get out of the woods," Bill said, "but if not, be vigilant and concentrate on any area that begins to hurt or becomes numb. Rub it, curl your toes." In the case that all feeling is lost, however, it's best to do nothing until medical aid is available. "Thawed out fingers or limbs are extremely tender," Bill explained, "and it makes it that much harder to get a victim out if he or she is in great pain."

Fortunately, accidents are the exception, and not the rule, though, considering all the implications of traveling above timberline, an inevitable question might be why venture forth in the first place? "There is a real sense of awe about being out in the harshest weather of the year, and a strong sense of accomplishment after a successful winter hike," Bill noted. "Also, there are fewer people around and you simply have to be more self sufficient. It's very special time, like foliage season. And like foliage, there are peak days, " he added. "if you catch one of those, it's a very special experience."

Comments